Metaverse at Enghelab Street

Tehran, Iran

2022

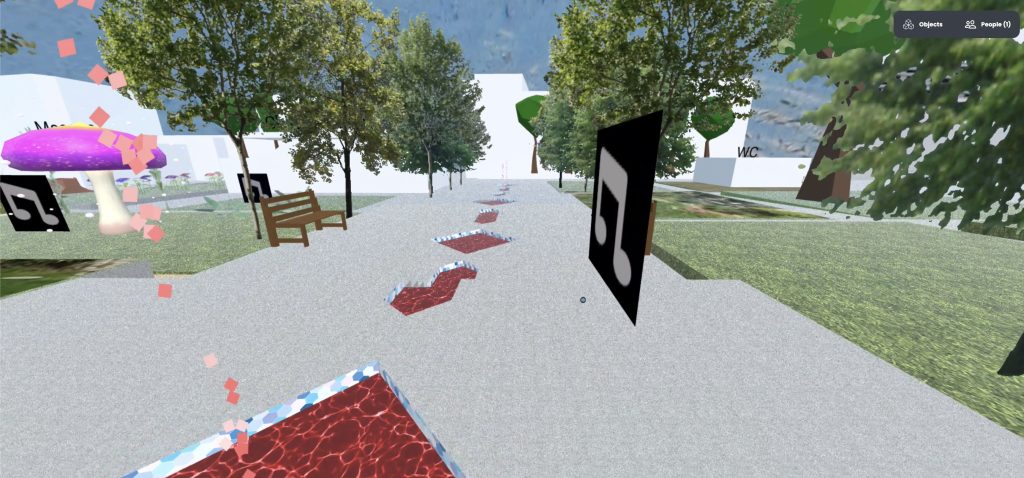

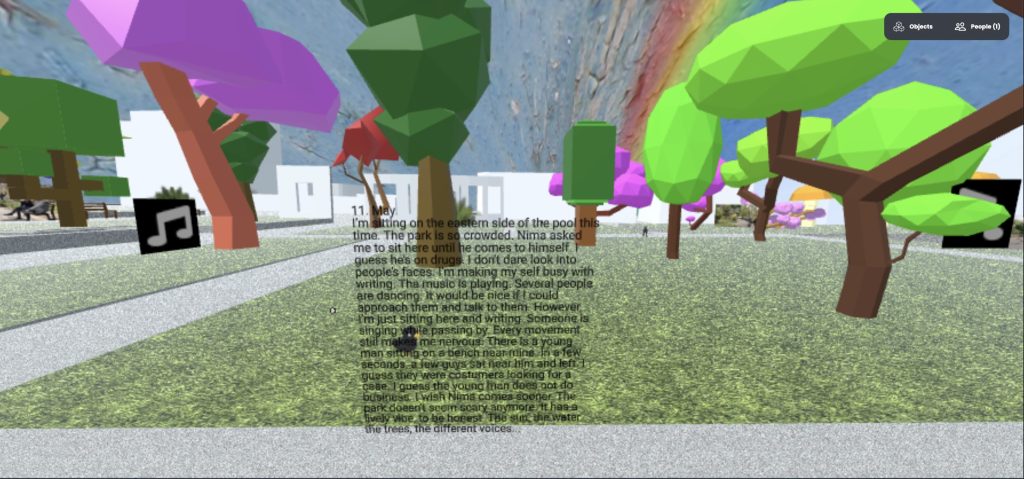

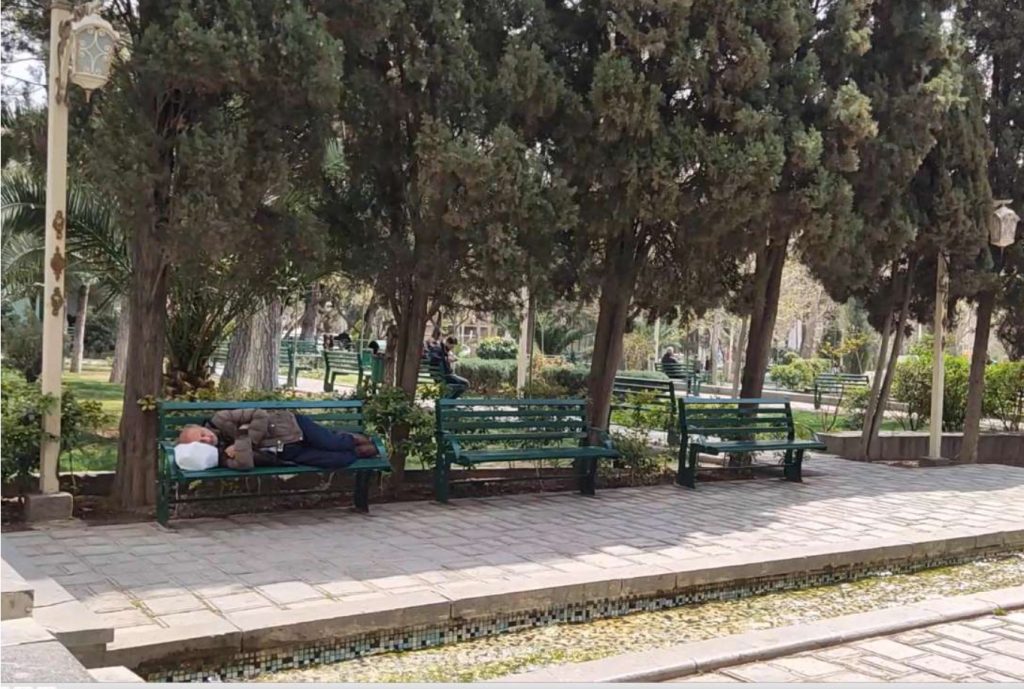

Located on Enghelab Street, one of Tehran’s most politically and historically significant streets, Daneshjoo Park has been a meeting place for the LGBTQ community, particularly gay and transgender individuals, since its establishment in 1967. Following the Islamic Revolution, the park has been subject to strict surveillance and various spatial interventions by the regime due to religious influence and the political climate, resulting in restrictions and the oppression of community members. Additionally, social stigma and discrimination have further marginalized these individuals, many of whom are also sex workers. Despite these challenges, the park remains one of the few gathering spots for sexual minorities to this day. The following project represents the park on an open-source virtual reality platform (Mozilla Hubs), featuring conversations with LGBTQ individuals from the park recorded in audio format during May 2022. The project includes videos and images capturing impressions of the location. The project’s primary goal was to provide a platform for people inside and outside Iran to hear these stories and raise awareness. Additionally, it aimed to create a safe virtual space for Iranian sexual minorities to meet and interact virtually. To ensure safety, the VR Park was not published publicly. Instead, private tours were conducted within the VR Park, accessible only to a limited number of participants each time.

Daneshjoo Park is a vibrant yet contested space, attracting a diverse array of social groups. Its central location and symbolic significance for the LGBTQ community draw various marginalized individuals. The park is a melting pot of artists, upper-class patrons from the City Theatre, sexual minorities, students, elderly locals, families, and a growing number of passers-by. Additionally, child laborers and drug dealers frequent the park, each group typically occupying distinct areas.

Significant policing efforts, including the establishment of a police station and the presence of plainclothes officers, have impacted social interactions, often targeting minorities such as sexual minorities and child laborers. Key interventions like the construction of a mosque, the metro station, and fences around the northern and eastern sides of the park have further shifted the park’s dynamics. These measures have enabled the state to dominate public spaces and increase control over the park. Consequently, these interventions have reshaped its physical landscape and intensified the battle over its symbolic and practical use.

These interventions have sparked conflicts, with different groups calling for the removal of others, including sexual minorities, drug dealers, and child laborers. These tensions mirror broader societal struggles between state power, civil society, and marginalized communities. The state’s use of space to assert control is evident, as various social groups contest their right to occupy and utilize the park.

Due to the slow internet connection in Iran, the VR model was designed to be highly efficient to ensure accessibility for Iranians. This required minimizing the size of the 3D model by using low polygon objects. Additionally, some parts of the park, such as the city theater or surrounding building blocks, feature abstract aesthetics. Instead of modeling every detail, images are used to optimize performance, such as the sculpture of the boys in the fountain. Consequently, the VR model is not a 1:1 representation of the park; it has a surreal quality, reminiscent of game aesthetics. The sounds heard in the model were recorded from the park and surrounding areas.